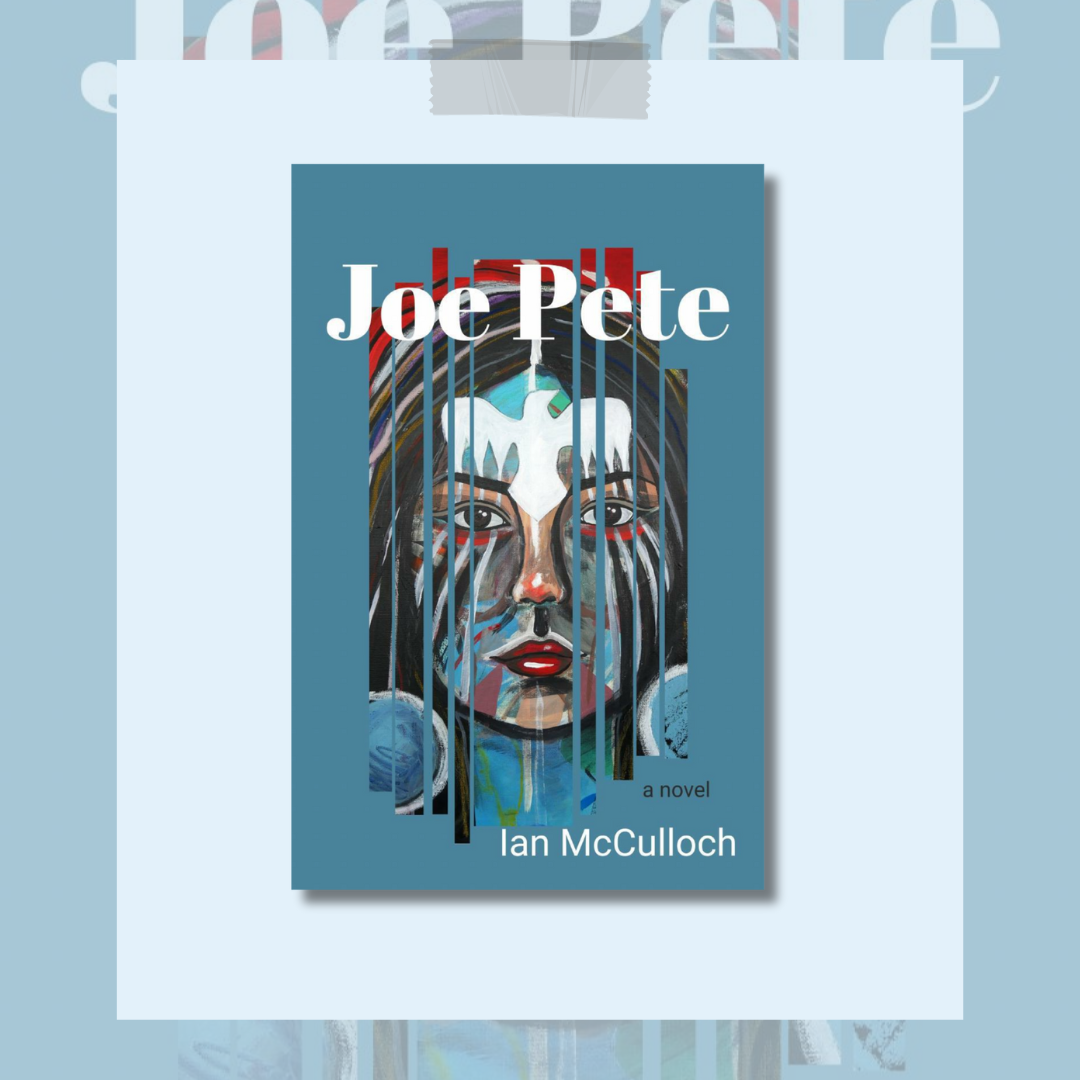

Joe Pete - Ian McCulloch

“Joe Pete”, published post mortem and written by Ian McCulloch, flew into my life to manifest itself as a truly beautiful work of indigenous literary fiction. The novel follows the story of an enduring Ojibwe family and their lasting bond over several generations, relayed via the emotional turmoil of eleven-year-old protagonist Alison. Nicknamed Joe Pete, she grapples with tremendous grief after losing her father who falls through the ice and is never to be seen again.

The book leads us through generations of family hardship, trauma, and above all, their ever present loss. I've never read a book that brings the searing ache of grief and the solace found in life's constancy together into such an authentic text. As a reader, I got the impression that the world is so very beautiful no matter the loss, because nature and its magnificence make up for it all. The sweeping scenes of a wilderness in its inert beauty probably also transform the reader's pain into a meaningfully deep experience.

“Her father taken from her and the fruitless search to find him … dominated their lives. The broken ice and the cracked sorrow that had come with the long dark nights of winter and how time itself had slowed in its passage like the snow-burdened river that had swallowed him.”

The vast nature, the glistening night snow, the biting, yet familiar, cold - these are all things I live for when reading Canadian literature. They make me relive my times in the North, when I waded through emotions and grief as deep as the impenetrable snow myself, only to look up and remember the moon who appeared all knowing and soothed it all. This book brought all that back to life for me.

“It is the deepest part of winter, dark and cold and a blizzard howls against the cabin and rattles the warped windows. The wood stove pops and cracks and throws waves of heat against them but still they can feel the wind on their backs. Mecowatchshish rides the turbulent air, high above, amongst swirling wind-driven snow looking down on what was once his home. He soars higher to take it all in. The landscape, the town that sits between the two frozen rivers.”

In my own experience with grieving the loss of a treasured family member I've sometimes thought that there's a quiet beauty in the aching pain. Because we hurt, we allow ourselves to fully focus on remembering the person without letting other distractions in. I've never much said this out loud because the mention of beauty might upset people who hurt. But this book feels like a validation of my innermost emotions because it mixes the grief that's omnipresent with such grace and resplendence.

“Day. Night. Day. Shadow and light. Up and up until he can see from James Bay to the Wolf’s Head of Superior all the land that is in his blood. Then down like the wind through the nebulous past, gathering the years he has known as he goes. Over the frozen river he moves catching up to a night, not so long past and sees his own footprints in the snow, sees where they end abruptly at a ragged fracture in the ice. The chill of the cold water lances through him and he is suddenly heavy with the sorrow of those he loved. He fights now to make it through the last stage dragging himself towards the cabin through the swirling storm resisting the pull to turn back.”

Joe Pete tries to hold on to her father by not allowing herself to let go of her memories. She continues to search for him, if not in flesh and blood, then instead in the spiritual truths of her heritage.

“It’s like the river, thinks the girl, and in her mind she sees the dark hidden water where it flows not far from them. Even under the snow and ice she knows it is moving, taking things away and imagining this, undulating shadows appear in her mind that she does not want. If only you could paddle upstream on this river of memory, she thinks. Fight the current to reach what you’ve lost, find an eddy that would allow for a few seconds, if only to say one thing.”

This spiritual search leads us to experience the conflict between the traditional beliefs of the indigenous people and the indoctrinated ethos of the English settlers in a time when a life without the latter is gone from memory. Alison, repeatedly told to leave these old ideas behind, can't stop herself from tracing her loss back to the roots she hopes to find. By attempting to revive her late father in this way, Alison unearths not only her own pain, but quietly learns that pain has been a companion throughout her ancestry.

In this realm, we hear about her father's feelings of grief in the Great War, about the loss of a boy at the hands of a violent stepmother, and more. Coincidentally, each of these losses appear to occur in the presence of white people, each expressing a clash in cultures and the aggressions that come with it. Even the oppression of one by the other is described, aptly, through a deep loss of connection to the self.

“His time in the Residential School he had begun to feel that connectedness slipping from him. There had been a vague, persistent premonition of it from the moment the train had begun to pull away from the station beginning the journey that would take him to the war in Europe. It had grown throughout his journey, in training camp, on the ship for England. Mecowatchshish often found himself looking at the men around him with a feeling of bewilderment. He was already Alexander McWatch and he did not fully understand how he came to be among them in their world.”

One aspect that's emphasized in the book is the usage of names. It almost got a little confusing because English and indigenous names are mixed, but then I found the very helpful family tree at the end of the book. I think the importance of naming is yet another avenue in which the book quietly expresses the many facets and meaning of indigenous culture. Joe Pete’s father Sandy, for instance, or Alexander McWatch, is really Mecowatchshish when the multiple layers of English indoctrination are removed.

The family stories told make the book come alive, so that the reader feels completely immersed and embraced by nature and love. The past is interwoven seamlessly with the present, and on a similar level, the character driven descriptions are interweaved with the advancement of the plot. Occasionally, this makes for somewhat abrupt transitions, but they made me think hard and analyze and understand the story better.

As a white reader, part of me kept hoping that the death of Dead Pete’s father would end up being written as a typical mystery. This kept me in suspense until the end. As the reader, I had to decide - do I allow myself to experience this book as an indigenous story, with an outcome that's possibly hazy, a world in which all things lost are never really gone? Or do I only allow a clear cut outcome to exist, one in which the mystery is solved, told through sequential thought and action, in only black and only white as we whites want things to be?

I got so much from answering this question. I received meaning. I got to experience how this magnificent culture finds answers to so many things in their ancestry. Their lost ones are in everything, live on in our surroundings. It made me realize that nature is full of the spirits of the once loved, and therefore full of love. Every tree and every stream holding space for us, for them, for humanity.

Thank you Ian McCulloch for this story. Its depth and all it invokes. Its love and its grace. Its unflinching, refreshing authenticity. Thank you.

In gratitude to River Street Writes and Latitude 46 for the Advance Reader's Copy. The book is actually published now, and you can read it for yourself already!